Since late 2020, the term “15-minute cities” seems to be the talk of the town in urban planning. Simply explained, it’s a city where everything you need is no more than 15 minutes away. But as with most labels, the reality is always more nuanced and — even prone to conspiracy theories, too. So is the 15-minute city just basking in its 15 minutes of fame right now, or is the concept here to stay?

We caught up with Dr. Benjamin Büttner, who heads both the Accessibility Planning research group at Technische Universität München, as well as EIT Urban Mobility’s Doctoral Training Network. He is also the author of the free online course ±15-Minute Cities: Putting People’s Needs First from EIT Urban Mobility’s Academy and helped us with this quickfire guide. Let’s see if you know about these 10 little-known aspects of 15-minute cities.

1. They’re years in the making

Carlos Moreno developed the concept of the 15-minute city in 2016, which gained attention after his viral TED talk in 2020. The idea of designing neighbourhoods where everything you need is close by has roots dating back a century. Clarence Perry proposed similar ideas in the 1920s, and transit-oriented development models have been around throughout the 20th century. Dr. Büttner adds that “In Germany, what used to be very popular was the Stadt der kurzen Wege, the city of short distances, some of which can still be found today. But with the 15-minute city concept, people could relate more and, in the end, branding was one of the keys to its success.” (Bonus: Learners can catch Dr. Büttner’s exclusive interview with Carlos Moreno in the first module of our course.)

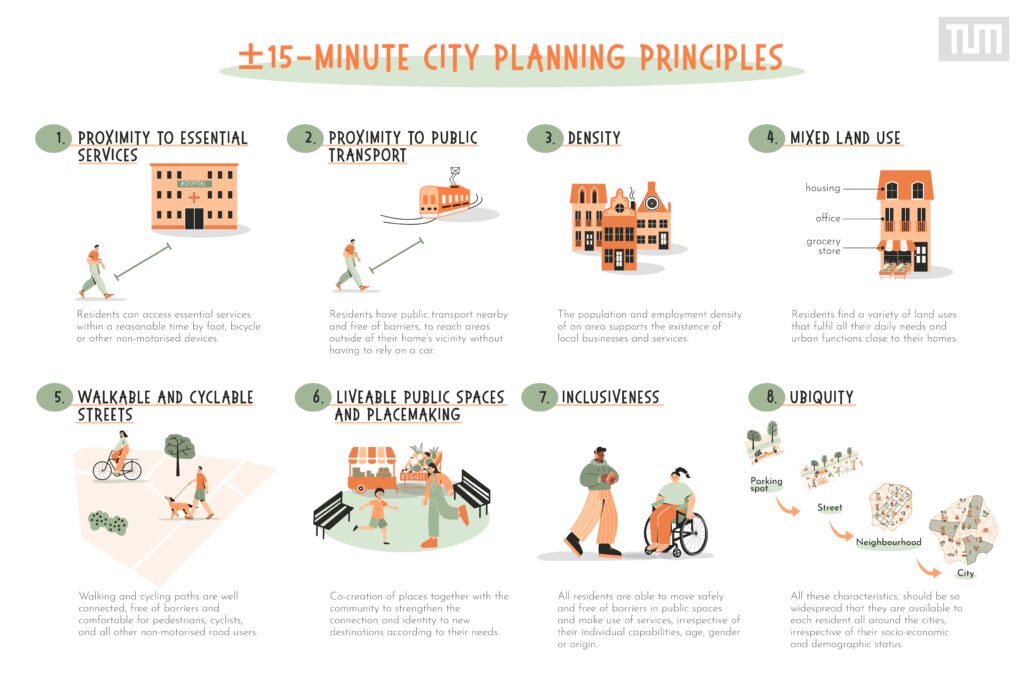

2. “Down to the minute” doesn’t really matter

Although the term “15-minute cities” implies close proximity to amenities, it doesn’t always mean that every service must be within a strict 15-minute radius. For instance, Melbourne’s “20-minute neighbourhoods” actually refer to the total time for a round trip, which effectively means that distances are about 10 minutes away. “Even Carlos Moreno himself isn’t too keen about the 15-minute threshold,” says Dr. Büttner. It’s why he and many other experts tend to add the “±” symbol to the name for flexibility. “The idea is that we should be able to fulfil or access our basic essentials within a short time period by active modes. You should just take this as an idea and then adapt it to your needs.” And yes, it can even apply to people living in spread out, car-dependent areas…

3. Not in a city? Even better

15-minute cities don’t just refer to cities, per se. Recent initiatives like Driving Urban Transitions (DUT) highlight the European Union’s commitment to funding the development of self-sustaining neighbourhoods, even beyond urban centres. “They see that these are actually the regions where people are the most car dependent and could benefit the most,” said Dr. Büttner, who has begun two projects focusing on transferring the 15-minute city concept to suburban areas. “Finding solutions here would be very important,” as experts try to establish a more holistic view of metropolitan areas.

4. Cars are welcome too

While 15-minute cities emphasise pedestrian-friendly environments and promote alternative transportation modes such as walking, cycling, and public transit, their aim isn’t to completely eliminate cars. Dr. Büttner remarked, “I think cars should have a place because they serve specific purposes, yet most of them are parked for 95% of their time and waste lots of space” — — space that cities could utilise more efficiently. Shared cars and underground parking lots for privately owned vehicles are effective alternatives for any city, not just those adopting the 15-minute concept.

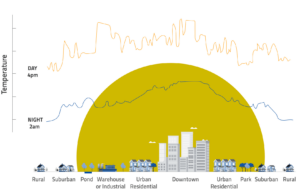

5. Healthy outcomes all around

You might already be aware that 15-minute cities promote sustainability by reducing car use, cutting emissions, and creating compact, walkable neighbourhoods that conserve resources and limit urban sprawl. “But what often is forgotten,” shared Dr. Büttner, “is that in car-centric neighbourhoods, people feel alone because they might not be able to go out or talk to their neighbours easily.” Given the increasing concern about mental health, socialising plays a crucial role in creating healthy cities. Moreover, with shorter commutes and more green spaces in new urban models, there’s greater encouragement for walking and cycling, which can reduce stress, improve mental health, and increase physical activity.

6. Where “smart cities” play a role

In 2010, the emergence of another term, “smart city,” actually motivated Moreno to explore shifting from a technology-focused approach to a more human-centred one in order to enhance the livability of cities. As Dr. Büttner elaborated, “technology can’t just be a crazy playground for techy people. It needs to benefit everyone to create something for the common good.” For example, while bike and car sharing apps can be terrific, they don’t take you very far if large swaths of the population don’t know how to use them. (It’s why “putting people’s needs first” is also in the title of our course.) “The smart city is only as smart as its citizens,” added Dr. Büttner. “For that, we have to listen and then find common ways of improving our cities.” Taking all of this into consideration, it follows that…

7. No two 15-minute cities look alike

Due to the diverse needs of citizens, the essential services and amenities may vary among different segments of the population. For a more comprehensive and fair approach, Dr. Büttner and his team suggest using a tool called Flowers of Proximity. “You can fill out your own flower,” he suggested, “and you can also see how older people’s responses compare to those of younger people.” For example, in one study, seniors prioritised access to markets whereas families valued the availability of schools. “We should use this tool to get in touch with people from all different kinds of backgrounds to change our perspectives and plan more inclusively.”

8. Quality over quantity

One factor that might hinder 15-minute cities from reaching their overarching accessibility and equity goals is the preference for quantitative methods over qualitative ones in measuring results. Dr. Büttner underscored, “A given model may say everything is okay” because a given amenity can be reached in 15 minutes. “But many don’t take into account factors like comfort and safety levels,” such as narrow sidewalks, car-filled bike routes, crumbling roads and more. “Counting minutes and activities might not tell you the whole truth,” he adds, “so you always need to go on the street and really talk to people.”

9. Commerce and gentrification

Some critics argue that the infrastructure needed to establish 15-minute cities is economically impractical and could harm commerce. Dr. Büttner noted that when superblocks, like those in Barcelona, were introduced, “local shop owners complained that no one would park in front of their shops anymore and business would decline.” However, eventually, vibrant atmospheres, propelled by walking and cycling rather than cars, actually stimulate more business, thus attracting investors. As these neighbourhoods become more desirable, Dr. Büttner emphasised the need to address potential issues with gentrification while also not compromising on urban attractiveness. Affordable housing for lower-income households is noticeably absent from most 15-minute city plans, which brings us to our final point…

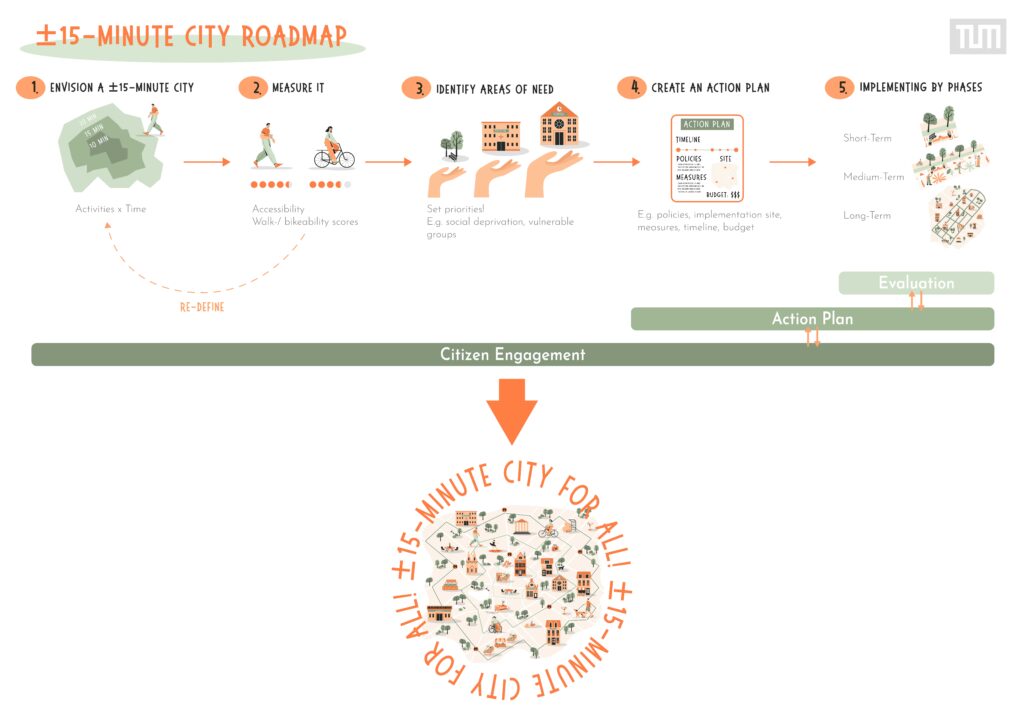

10. They still need work

Buzzword status aside, the 15-minute city is not set in stone. “It’s a concept, not a blueprint,” Dr. Büttner pointed out. He concluded that more people should be involved in adapting 15-minute cities to address issues such as accessibility gaps and gentrification. “It’s not rocket science but we cannot do it alone. We have to find allies — and what better allies can you find than your neighbours who also want to improve the situation?” So what are you waiting for? With so many people you can reach in just 15 minutes, the possibilities are limitless. The roadmap that Dr. Büttner and his team created, along with our course, are a great place to get started.

Adina Rose Levin

Adina Levin was born and raised in Chicago, and clocked in over 10 years in New York City before moving to Barcelona. As a freelance writer and creative strategist, she explores cities, culture, media and tech.

Dr. Benjamin Büttner

Dr. Benjamin Büttner is Head of EIT Urban Mobility "Doctoral Training Network" and Head of TUM Research Group "Accessibility Planning"

Illustrations reference: Büttner et al. 2022 (Büttner, B., Seisenberger, S., Baquero, M., Rivas, A. Haxhija, S., Ramirez, A., & McCormick, B. 2022. In: Urban Mobility Next 9. EIT Urban Mobility).