A primer on UVARs (Urban Vehicle Access Regulations)

You might have heard of terms like “Low Emission Zones” or “Congestion Pricing,” but did you know that they are part of a larger toolkit that cities use to manage urban traffic and reduce pollution? Known collectively as Urban Vehicle Access Regulations (UVARs), these measures vary in approach and impact, offering different opportunities and challenges to create healthier, more efficient, and livable urban spaces.

To better understand UVARs, UMX spoke with Lucy Sadler, who runs the European Access Regulation Platform and the air quality and transport policy consultancy, Sadler Consultants. Previously, she was the head of air quality for the Mayor of London, with whom she worked directly on the Central London Congestion Charge and London’s Low Emission Zone. She’s also the author of our online course Mastering Urban Vehicle Access Regulations for Sustainable Cities (UVARs), where you can learn more about this topic for free.

What is an UVAR?

Urban Vehicle Access Regulations or UVARs (pronounced “OOH-vars”) are already a priority area of the new EU urban mobility framework, even though the concept only became codified rather recently. That’s probably why it’s not (yet!) a buzzword in urban mobility. In a nutshell, “UVAR” is an umbrella term that covers a suite of interventions that tackle congestion, noise, and pollution in cities. As Lucy put it, “There are lots of policies that try to nibble away these problems, but you often have to use a bigger hammer to have enough impact.” Think of UVARs as a set of tools that can be used on their own or together to help cities hammer away at emissions and congestion and get to climate neutrality.

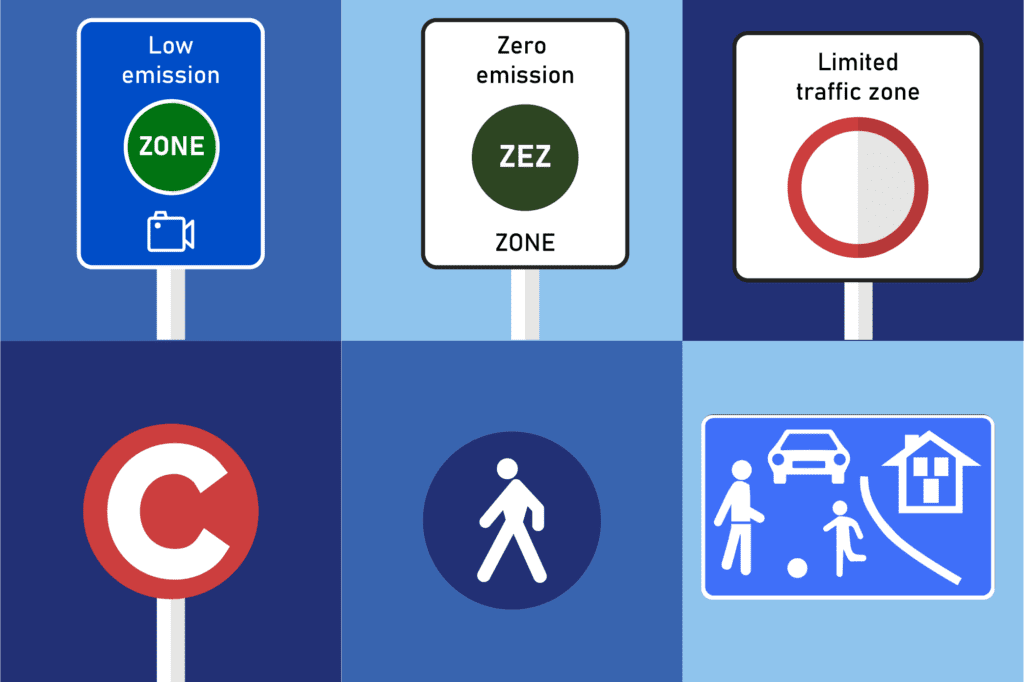

Common UVARs include:

- Low Emission Zones (LEZ): Areas that restrict high-emission vehicles.

- Limited Traffic Zones (LTZ): Areas with restricted vehicle access based on permits, which depend on factors like vehicle type, emissions, or time of day and/or week.

- Zero Emission Zones (ZEZ): Areas that allow zero-emission vehicles only.

- Congestion Charges & Urban Tolls: Fees for entering city areas.

- Pedestrian Zones: Vehicle-free areas.

- Spatial Interventions: Road modifications like bus lanes and traffic filters.

If some of these interventions sound like they overlap with projects such as superblocks or car-free zones, you’re not wrong. It’s all a matter of framing. Lucy explained that UVARs boil down to two overarching frameworks: “You can either ban and/or charge vehicles so that there are fewer total vehicles” (like in interventions 1-4 above), “or you can take space away and the remaining vehicles will eventually change over to alternatives because the area will be too congested” (like in interventions 5-6 above). Furthermore, “Some definitions of UVARs,” Lucy continued, “include parking regulations, too, because people will stop driving into an area if they can’t park there.” While our UVAR course doesn’t go into much detail on parking, here are some helpful accounts to follow, and check out our UMX blog for more on curbside interventions.

It’s precisely the range of options that make UVARs so essential for cities. UVARs don’t necessarily require a huge overhaul either; they can be done bit by bit and even stealthily. “Doing a spatial intervention like a one-way street is not particularly controversial,” Lucy explained. “But a congestion charge is usually very controversial.” Just ask New York City. Ultimately, UVARs are about preventing vehicle access “but at the same time,” as she pointed out, “ensuring that the people and goods can still get there so that the city can still thrive.” With a menu of potential solutions at their fingertips, planners can design a UVAR that best fits their cities’ unique needs. So… where to start?

Choosing the right UVAR for the job

As is the case with many public works, data-driven decisions are critical to showing cities the way forward. As Lucy put it, “You don’t do a low emission zone for lorries only to find out the problem was vans.” Robust investigations and stakeholder dialogue on the potential impact of UVARs should also factor in. For example, vehicle restrictions and charges can hurt those who can’t afford to pay or purchase a new vehicle, which is why grants and additional public transportation options must be added to the equation.

Once you establish a regulation, naturally everyone will ask for an exemption. “Then you have to use good judgement to work out which exemptions are reasonable,” Lucy advised. “Which vehicles need to be there? Not commuters — but ambulances, buses, deliveries, street cleaners, among others, should be granted permits for limited traffic zones.” In some cities, limited numbers of permits (e.g. up to 12 a year) can be purchased so that one-off approvals, such as for moving house or “taking granny to the doctor,” don’t slow down the system. However, Lucy was quick to add that while permits can be short- and long-term, they should never be permanent. Our streets are constantly changing, yet you can’t change permits after you’ve issued them.

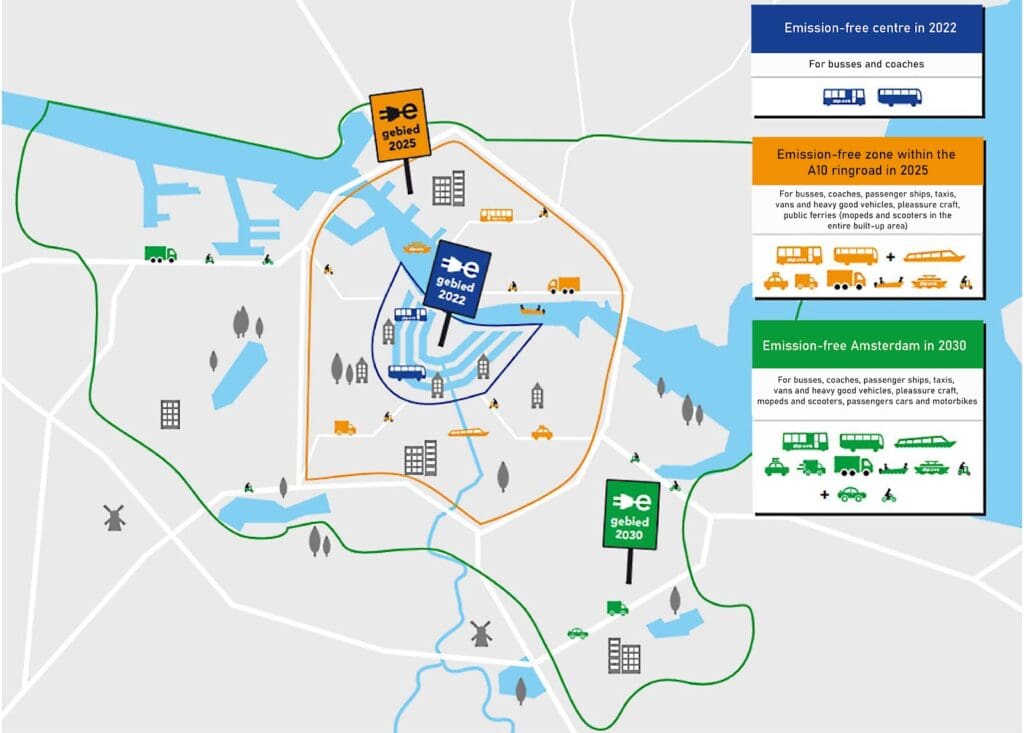

Exemptions also depend on the kind of UVAR. ”There are increasingly combined schemes, like charging non-compliant vehicles in low emission zones instead of banning them,” Lucy remarked. “So that if you want to come into the area with your old, high-emission car once a month, it’s worth paying the fee. But if you want to come in every day, you’d soon find it too expensive.” That’s the approach the Central London Ultra LEZ took with their Low Emission Zone (LEZ). Antwerp carried out a variation on this, allowing vehicles that meet specific emission standards to purchase 12 entries a year. Moreover, most LEZs are phased, meaning that they gradually make their restrictions stricter. “If you don’t tighten an LEZ, the natural fleet renewal will catch up with the LEZ standard. You always have to be a step ahead and publish standards well in advance so everyone knows what to expect and can plan for it.” Other cities whose UVARs that Lucy highlighted include Amsterdam, Ghent, and Barcelona — plus, you can create your own UVAR for your city using the ReVeAL tool mentioned in our free UMX course.

How storytelling sells UVARs

Let’s face it: Cities won’t cut down on emissions on their own. It’s citizens like us who need to be nudged. “In your own life,” Lucy explained, “there are three reasons you do things. One, because it’s cheaper. Two, because it’s more convenient. And three, because you have to.” In other words, even when we know we really should go by public transit or bike, many of us will still take a car as long as it’s still an option. While UVARs can serve as a “boot in the butt” toward climate neutrality, they can’t be implemented on their own: They must also provide alternative modes of transport to access the area. Again, Lucy stressed, “We don’t want to lock out people or goods.”

That said, even with alternatives and specific, strategic exemptions in place, UVARs are likely to encounter resistance from the public. Lucy pointed to the public acceptance curve, detailed in our free course, to understand what happens: “When people first hear about a new intervention, it sounds like a good idea… Until they get more information and realise it’s going to affect them. Acceptance will only go up afterward if the intervention has been done well, but politicians can get scared because the dip in acceptance tends to coincide with opening day.” After all, public opinion and city planning depend on each other, which means cities should get creative with their storytelling for UVARs and “take the people with them,” as Lucy liked to say, to get the happy ending our cities deserve.

Diagram of the public acceptance curve (EIT Urban Mobility)

Thankfully, there are several cities that planners can look to for inspiration. For example, to implement a low emissions zone in Jerusalem, politicians first had to make pollution strike a chord. The city’s air, once famously celebrated in the local anthem “Jerusalem of Gold”, with the lyrics, “The mountain air is clear as wine,” has become heavily polluted in recent years.

This prompted the administration to launch an awareness campaign about pollution that shifted public perception to look favourably upon the city’s planned LEZ.

Lucy cited another example, “A tale of two cities: Stockholm and Gothenburg.” Both introduced a congestion charge, yet whereas the former explained to its citizens that the scheme was to reduce congestion and that the money earned would go toward transportation, the latter focussed on the charge to fund the construction of a new tunnel. Lucy remarked, “Can you guess which one was successful in terms of public opinion and which one wasn’t?” Stockholm’s congestion charge “has become more successful and popular with every year that has passed”; Gothenburg’s “still attracts criticism 10 years on.” Yikes!

These cases also point to the responsibility of politicians, policymakers, and planners. After all, difficult stories call for a master storyteller. Lucy noted that UVARs “need a champion — someone who says, ‘I want to make this happen so I’m going to make this work’ and carry it forward.” Someone who isn’t afraid to take charge of initiatives like low emission zones and congestion charges, as unpopular as they might be at some point in the public acceptance curve, and set a new narrative that sets the city up for success. Now that you know more about UVARs, perhaps that person can be you!

Adina Rose Levin

Adina Levin was born and raised in Chicago, and clocked in over 10 years in New York City before moving to Barcelona. As a freelance writer and creative strategist, she explores cities, culture, media and tech.

Lucy Sadler

Lucy Sadler is a world expert in Urban Vehicle Access Regulations (UVARs). She was the head of air quality for the Mayor of London, working on the Central London Congestion Charge and London Low Emission Zone.