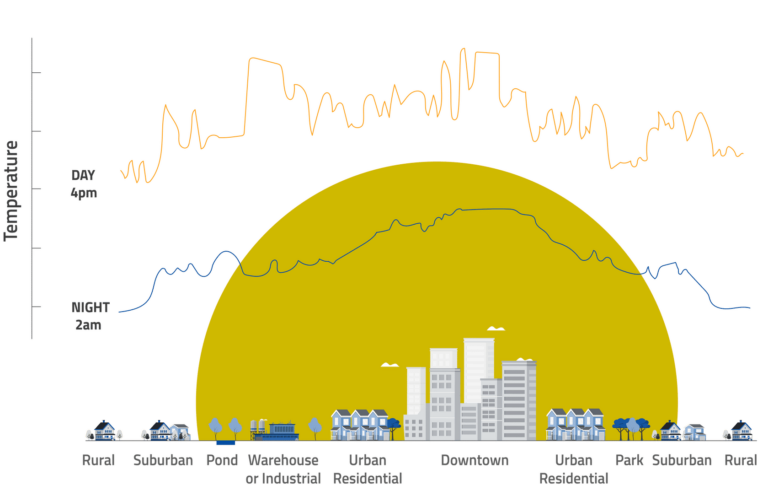

It’s not just you: Summers are getting hotter from climate change. In particular, cities like yours are in the heat of it because of the urban heat island effect (UHI), which exaggerates warm temperatures, especially at night when spread-out areas get a much-deserved cool-off. So what can concrete jungles do to beat the heat?

UMX consulted with Carlota Sáenz de Tejada, a postdoctoral researcher at Barcelona Institute for Global Health (ISGlobal) and author of UMX’s free online course The Urban Heat Island effect: How to tackle excess heat in cities. There’s no blanket solution (who would want a blanket anyway in the heat?!) but there are several specific strategies that we can start putting into action for both immediate and long-term results.

It’s beyond climate change. It’s a design problem.

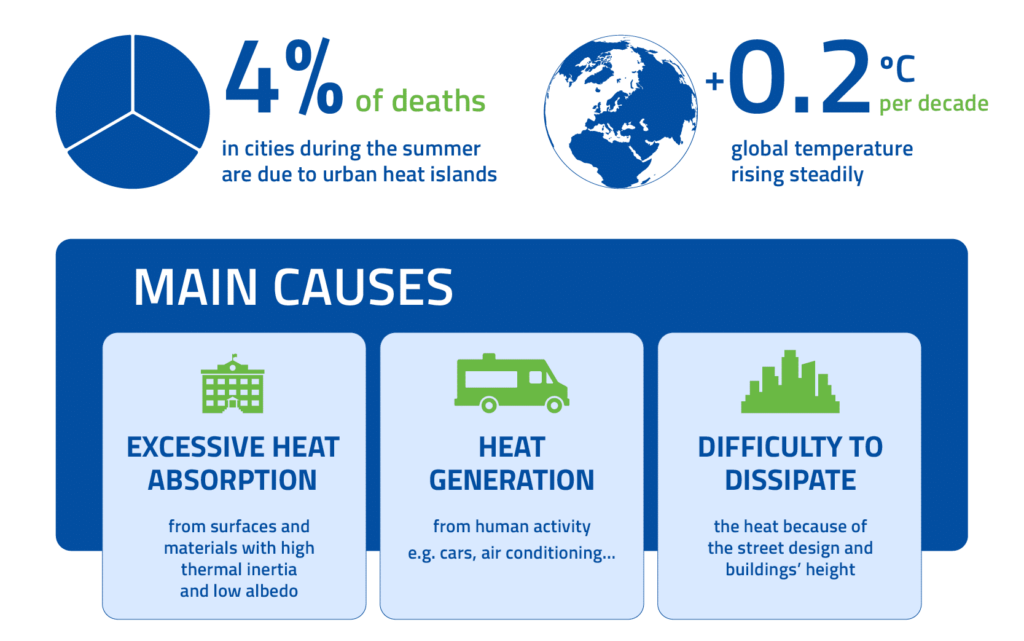

Urban heat islands (UHIs) aren’t another way of describing climate change, rising average temperatures or more frequent heat waves. They’re related but, as said Carlota, “UHIs are really about how our cities are built and designed,” and how those elements make it feel hotter in the city, before we even reach the dog days of summer. Then, factor in climate change and the problem gets a lot worse for city dwellers.

As Carlota continued, the UHI effect is essentially “an overheating dynamic caused by an excess of materials like asphalt, a lack of green cover, and other problems, such as our use of cars and air conditioning, which also generate additional heat.” Put all of these elements together with a dense urban configuration and that heat is trapped. As a result, the city centre gets much warmer than its surroundings, leading to increased tropical nights, when temperatures stay at or above 20°C (68.0°F). This can take a toll on our health, with serious repercussions for parts of our population that are already at risk.

(To learn more about the important health aspects of urban heat islands, check out UMX’s 2023 webinar with ISGlobal’s Carolyn Daher on Urban Heat Island: Strategies)

Think green solutions — and white ones, too.

It likely comes as no surprise that the main strategy for combating UHIs in the concrete jungle is increasing urban green infrastructure, ideally with at least 30% green cover. Yet as Carlota was quick to point out, “30% is not meant to be the city average, but rather a minimum for every neighbourhood to guarantee distribution of access to green areas for all residents and avoid intra-city urban heat islands.” Aside from the fact that trees can be time-consuming to grow and maintain, it’s even more challenging to add greenery in compact cities, where there are several limitations to updating existing infrastructure, let alone available space to begin with. That’s why cities must get creative with solutions detailed in the course, such as green walls, green roofs and planters, like this recent EIT Urban Mobility challenge in Riga.

In a similar vein, the 3-30-300 rule of thumb to increase green cover is gaining momentum. According to Prof. Cecil Konijnendijk van den Bosch, “every citizen should be able to see at least three trees (of a decent size) from their home… have 30 percent tree canopy cover in their neighbourhood… and live 300 metres from the nearest park or green space.” A 2022 paper by researchers from ISGlobal and other Spanish research institutions showed that this rule of thumb was associated with “better mental health indicators” even though not enough parts of Barcelona complied with these conditions. As Carlota elaborated, “it’s hard to meet the three of them at the same time in compact, high density cities — and that is what’s most beneficial because it works at these three scales to avoid having a big chunk of green that only benefits those who live nearby it.”

Another important concept is permeability, in other words, replacing asphalt with soil-based grounds that act like “sponges” to absorb the humidity that makes it harder to sweat and cool off. Think about it, “if you stand on the grass,” explained Carlota, “it’s going to be a lot cooler than if you stand on the pavement — and soil also stores moisture in a way that helps cities better manage stormwater,” which is becoming more common with climate change. Yet it’s very expensive to get rid of asphalt, particularly in cities with complex underground systems, and soil is hard to encounter naturally in highly built-up areas. That hasn’t stopped cities, like some in North America, Europe and Australia from trying! “It’s about reducing artificial paving to a minimum,” Carlota remarked, “and trying to leave as much space for green to grow as possible.”

As for frugal and immediate results, ancient architects in Southern Europe were on to something when they painted their buildings all white, shaded their indoor patios and took advantage of orientation and wind flows to make it feel less hot. Carlota commented, “It’s incredible that northern areas are now applying strategies that were traditionally applied in warmer areas.” She referenced the map in our free course that shows how, for example, London in 2050 will feel like Barcelona right now. Indeed, some cities like Los Angeles are already literally painting the town to reflect the sunlight. “It’s a low-cost solution,” said Carlota, “and I lived it in my own building! I was on the top floor in Madrid’s city centre, and when they painted it white and I could really notice the difference.

Sweating the details: How to get the job done

As you can also imagine, these UHI solutions come with complications. After all, what may work well to cool cities off in the summertime could backfire when residents want to stay warm in the winter. Carlota mentioned how “cool roofs and lighter colours can be good in the summer, but studies found that they might be at risk of increasing the energy demand for heating in the winter. The same goes for green walls,” which is why we need further research to understand the needs of specific communities.

Other concerns that commonly arise include cost and maintenance. Again, Carlota emphasised, “We need more solid evidence — maps that show decision-makers how investing in these physical changes to our cities can actually avoid the health-related costs associated with hotter cities,” resulting in both net savings and lives saved. While health is a strong motivator for change, a healthy bottom line makes it possible to bring change to fruition. Yet budgets tend to be divided by service, with tree planting and management disconnected from healthcare and social programs. Carlota advocated for “more transversal, holistic ways of understanding and collaborating in the design of our cities,” as cited in another ISGlobal study led by Tamara Iungman that showed that if trees covered 30% of urban space, a third of UHI-related deaths could be avoided. “But in the end,” Carlota added, “how do you get to 30% green cover” if private owners and developers aren’t motivated to contribute too? Some municipalities, like in Vienna and Singapore, have found it useful to create regulations and incentives like funding for the private sector to increase green space.

Carlota remained hopeful as she reflected on the growing awareness of UHIs to make this issue a priority. “Previously, we only thought of heat exposure as uncomfortable,” she noted. “But now, administrations are coming up with urban cooling plans and indexes for heatwaves as well as urban heat islands” that are backed up by research on the health impacts. Carlota also stressed that policymakers take a personal perspective as to how behaviours adapt to hotter climates: “We know that people go outdoors less to avoid the sun and they also take public transport less, favouring cars with air conditioning. It’s those who do not have any alternative and who have no choice end up suffering most.” Putting people at the centre, which our free course elaborates on toward the end, reveals that even shady spots and so-called shaded itineraries can make the heat somewhat bearable. “Thinking about how people would actually move through the city and making it more comfortable for them considering these high temperatures contributes to promoting overall green cover.”

Adina Rose Levin

Adina Levin was born and raised in Chicago, and clocked in over 10 years in New York City before moving to Barcelona. As a freelance writer and creative strategist, she explores cities, culture, media and tech.

Carlota Saenz de Tejada Granados

Carlota works as a postdoctoral researcher at the ISGlobal Urban Planning, Environment and Health Initiative and is a collaborative professor at Universitat Oberta de Catalunya (UOC).