When taken as a whole, private motorised vehicles are among the world’s biggest polluters, so it might seem odd that some cities are doubling down on individual car usage to become more sustainable. But it’s the “shared” aspect of these new initiatives that has climate stewards cheering. After all, sharing cars can reduce the number of total vehicles on our roads and streets, leading not only to a decrease in emissions — even more so when you replace them with EVs — but also to less car dependency and more optimised use of urban space.

We caught up with Anna-Richt Hannema, who runs Kartrekker in the Netherlands, to give us more insights on how cities can embrace cars for sharing (instead of launching an “imaginary war on drivers”) to support the transition to a greener future. She and Ananda Groag are co-authors of the free online course on Car sharing: the smart way to drive from EIT Urban Mobility’s Academy, where you can learn about this topic in greater depth.

Shut up and drive: More occupancy, less ownership

As fancy car commercials continue to sell you the dream of owning your own car, here in Europe over half of all households already own at least one. Yet even as motorisation rates continue to rise, the reality is that you’re more likely to see cars lying motionless on a street rather than zooming along an empty highway against a gorgeous landscape, nor are the traffic back ups as widespread as the media might make you think. The reality is that “Owned cars are parked or go unused for over 95% of the time!” says Anna. She also adds, “A lot of people own two cars, and the utilisation rate for second cars is even less,” leaving a lot of wheels spinning.

Data on shared cars are hard to come by because most car sharing service providers are private and don’t share their data publicly. But based on Anna’s own work for car sharing initiative Ons Buurtschap, the contrast is already significant. “A generally known minimum occupancy rate required for such service providers to operate at a profitable level is 25%. On average, occupancy rates for shared cars will range between 25-40%.” That’s compared to the 5% that owned vehicles are in use, regardless of how far they drive.

More specifically, it’s drivers who tend to make local trips for whom car sharing tends to reduce car dependence in general. As Anna puts it, “Car sharing has the effect of promoting around a 20% decrease in use of cars as mode of transportation, as well as a decrease in total kilometres travelled, especially within the travelling distance range of 0 to 10 kilometres. Many people who expressly opt for car sharing get rid of their first and/or second car.” Her numbers also support the following findings from CoMoUK: Each car sharing vehicle can replace approximately 9-13 private vehicles and, furthermore, among those who adopted car sharing, 25% of them opted to sell their private vehicles, while another 25% deferred the purchase of one.

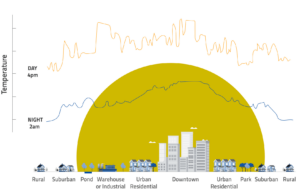

In short, car sharing serves as a catalyst to support the transition to more sustainable forms of mobility because once drivers become shared car users, they also begin to rely more on walking, biking and public transportation. The move also drives a shift to more multimodal transport, such as driving a shared car to get to or from a train station between cities, or in a neighbourhood with fewer modal options. As a result, Anna says, fewer total movements by car leads to “less congestion, pollution, noise and stress and generally improves the quality and liveability of the urban environment.” And there you have it, right? As it turns out, there’s a lot more to the sustainability equation.

Driving a hard bargain: Where local governments come in

However, all of these environmental benefits of car sharing are predicated on good conditions for the market to thrive. Anna points out that a reduction in car dependency “is greatest when it is properly leveraged by social car sharing concepts in tandem with local policies facilitating — and even incentivising — car sharing successfully.” Local governments must nudge people toward car sharing in the first place for the programs to impact the environment because you can’t count on market forces to understand everything at stake.

“Commercial companies are not there to solve environmental problems. They are aimed at profit maximisation, which will always drive toward car consumption maximisation. So even if we could accomplish all current car travel by commercially shared cars, we could end up with a problem in the urban space bigger than before. Local governments can benefit by cooperating with social car sharing concepts for purpose-filled entrepreneurship, taking improvement of the urban living environment as a common goal and taking into account not only the economic values but also the social and environmental impacts.” —Anna-Richt Hannema

These government- and citizen-led car sharing concepts can look different depending on the region. For example, when the Belgian national government determined that local authorities needed to offer two shared cars for every 1,000 inhabitants, the citizens-led, cost-sharing peer-to-peer car sharing platform Dégage was born, and now it operates 400+ cars for 5,500+ drivers across nearly 40 municipalities. Or in Bremen, Germany, local authorities and citizens worked together to replace 6,000 privately owned cars and get 20,000 car share users by 2020. (You can explore both of these examples and more in our free course on car sharing.)

Freedom to drive — and free up public space for better uses

The environmental benefits of car sharing go well beyond emissions and can also lead to — or be instigated by — changes in the urban topography that support overarching sustainability goals. “As car sharing tends to reduce the number of cars,” Anna shares, “this enables local governments to repurpose the significant amount of public space currently allocated for parking cars.” In other words, for every space that used to be parking or an entire parking lot, alternative uses such as green space, playgrounds and spaces for social interaction can be added for consideration.

In the realm of urban (re)planning, Anna references how forward-thinking initiatives like the Superblocks in Barcelona and car-free neighbourhoods such as Merwede in Utrecht, Netherlands, underscore the transformative impact of reducing private car ownership. Even smaller initiatives like car-free days in Paris, the Leefstraat (“The Living Street”) in Ghent and the Parklets campaign in London showcase the potential for reclaiming public areas from cars for community engagement, greenery and recreation.

Actively promoting car sharing aligns with these best practices by fostering a shift from traditional car-centric designs to embrace mobility hubs and shared solutions in last mile logistics. These initiatives not only raise awareness but also offer tangible experiences that are already contributing to a global dialogue on sustainable urban development where car sharing has a welcomed spot at the table.

How car sharing can drive the energy transition

Saving perhaps the most obvious point for last: Car sharing can be even more sustainable when electric vehicles (EVs) are used instead of traditional fossil-fuel vehicles. Yet the drawbacks of purchasing electric vehicles, such as high costs and infrastructure challenges, are significant, despite some interesting use cases like using lamp posts to charge EVs. Furthermore, as Anna adds, “electric power still needs to be generated somewhere, so shared EVs only reduce local emissions,” making car sharing concepts that lean on EVs are inevitably harder to bring to fruition.

Many initiatives get stuck, and this is where the government can come back into play. “Their impediment is firstly the difficult business case for electric car sharing and the scalability of their business model,” says Anna. “Local governments could help if their tenders would consider value creation in its multiple faculties — economic, social, environmental and even systemic — and financial streams were rerouted accordingly” to take into account and then reduce the actual costs to the urban living environment that privately owned cars currently generate.

So what if EVs could actually serve as more than just cars but actual mobile batteries for the energy ecosystem? “Buffering” is exactly that: Using EVs to store excess energy in a neighbourhood’s grid during peak times and contributing back to the grid during high consumption. “Although the potential as an energy buffer principally pertains to all electric cars, both shared and privately owned,” Anna says, it may be more beneficial to work together with car sharing initiatives toward this purpose.” EV fleets can not only serve as potential energy buffers, aiding the transition to renewable energy, but partnerships between car-sharing initiatives and renewable energy companies can accelerate the shift to entire sustainable cities, like WeDriveSolar in the Netherlands.

Yet at present time, the full potential of electric car sharing is hindered by inadequate infrastructure, including a shortage of charging stations with bi-directional capabilities for renewable energy buffering, dedicated parking spaces and optimised power grids. Anna notes that local governments are crucial players here too. “The technology itself is ready but local governments’ commitment to integrating innovative, long-term solutions faces challenges when it comes to integrating the available, innovative solutions, as the choices entail complexity.”

Ultimately, effective stakeholder collaboration with car-sharing programs is essential not only to the financial viability of electric cars but also to securing our much-needed transition to sustaining living environments as cities continue to grow. Unlock practical strategies to implement thriving car sharing initiatives in your community with EIT Urban Mobility Academy’s free online course.

Adina Rose Levin

Adina Levin was born and raised in Chicago, and clocked in over 10 years in New York City before moving to Barcelona. As a freelance writer and creative strategist, she explores cities, culture, media and tech.

Anna Richt Hannema

Anna-Richt Hannema is a self employed shared mobility expert at Kartrekker. She is co author on EIT Urban Mobility Academy´s Car Sharing online course.