Car dependency is one addiction that you literally can’t just kick to the curb. The shift from polluted, congested, and car-dominated cities to more sustainable ones requires multilayered strategies. Simple yet integrated mobility hubs that turn shared mobility and public transport into the most convenient transit options can help cities reboot their mobility patterns. But that depends on approaches that hook people on greener transport and avoid gridlock, both on the road and among city stakeholders.

UMX spoke with Jens Müller, a freelance sustainable mobility consultant currently serving as Deputy Director for the Clean Cities Campaign from the European Federation for Transport and Environment (T&E) to clear up the hubbub about mobility hubs. He is also the author of UMX’s free online course Implementing Mobility Hubs to Reduce Car Dependence in Cities. With his insights, we’ll uncover essential elements that enable mobility hubs to steer cities away from car dependency without costing them their bottom line.

The power of choice: Why multiple options matter for success of mobility hubs

As with food, entertainment, and all of the other finer things in life, people want options — and transport is no different. Jens cited Michael Glotz-Richter as one of the first experts to understand this idea as it related to mobility hubs and shared cars in Bremen. Even research from Uber found that people don’t tend to give up their cars unless they have at least four transport fallbacks, particularly as shared e-bikes and e-scooters as well as rideshares have become popular.

But what makes an alternative transport option attractive enough to compete with private cars? According to a 2019 European Commission survey, it boils down to three key considerations: comfort, speed, and reliability. “All three of them can be tackled, to a certain extent, by mobility hubs,” Jens remarked. “It’s comfortable and reliable when you can always find a shared car or bike close to your home when you need it. Speed can also be enhanced when you don’t have to spend time looking for the places to pick up and drop off the vehicles.” The same thing applies to comfortable, quick, reliable public transport at mobility hubs as well.

However, offering additional transport options is no guarantee that people will make the switch from cars. As Jens said, “You will probably not convert 100% of all the private vehicle drivers that might be open to it, but backups at least get us as close as possible.” Moreover, each city has its own needs and mobility habits based on factors like geography. Jens compared Finland to Spain: Even though both cities offer cycling, the hubs would not look similar considering that the bikes would be used under different conditions, such as extreme cold vs. extreme heat, and successful examples of mobility hubs exist in both countries.

Simple tips for mobility hubs that shine

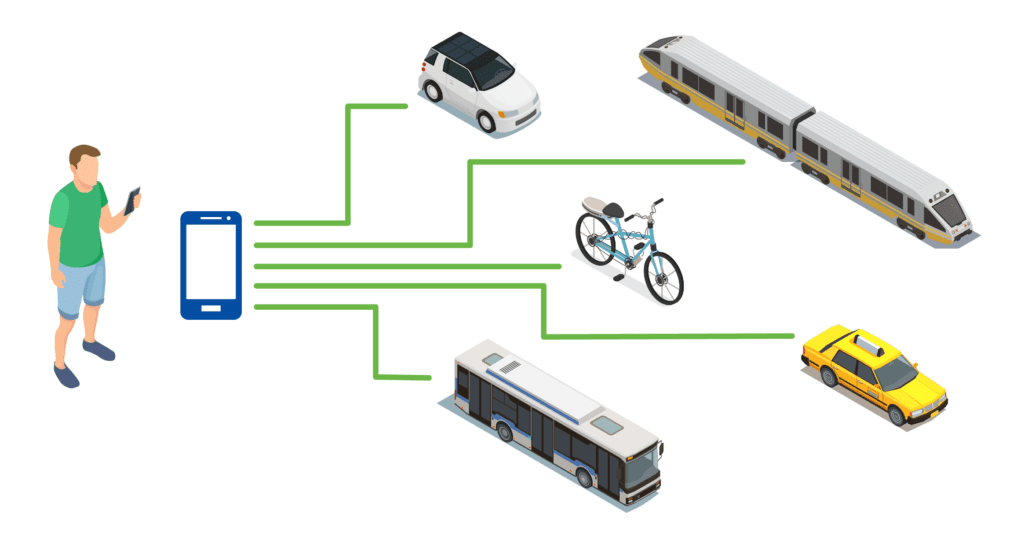

Before going any further, it’s important to emphasise that not every combination or conglomeration of transport options qualifies as a bona fide mobility hub. “It’s not about putting a nice sign next to a bus stop and calling it a mobility hub because you can attach your bike or there’s a nearby car sharing station by coincidence,” Jens explained. “Nor can a mobility hub just be randomly in a square or available virtually on an app. These things in isolation probably won’t have an impact.” True hubs must be dedicated, physical spaces where different mobility alternatives are integrated. “Mobility apps can help create the idea that these modes belong together,” but more on that piece later…

Hubs usually revolve around a solid public transport network, which thankfully many European cities already have. Yet everyone knows that at peak hours buses and trains get uncomfortable, and at off-peak hours they tend to run as less frequently. “That’s exactly where shared modes can complement more traditional ones,” Jens highlighted. “When the tram is too crowded or there’s a strike or it’s the middle of the night, you can refer people to other modes of transport that can be cost-effective for a city to operate.”

To make mobility hubs shine, cities should put these spaces in the spotlight. “A hub has to be recogniable so that you don’t have to always get out your phone to look for the place,” Jens continued. Good messaging goes a long way, too. In addition to what he called “signposting,” Jens mentioned incentives like integrated pricing. “Show the benefits of combining transit options, that it becomes cheaper to use these alternatives,” Jens added as he mentioned how Dresden cross-sells its mobility options at a discount to anyone with a subscription.

Mobility hubs can’t be temporary either. Jens acknowledged that “in urban planning and transport, we tend to see lots of pilots and trials. But if people feel like a mobility hub will be gone next year, nobody will give up their car.” While there can be exceptions, such as temporary mobility hubs for large events, people require long-term solutions in order to make the long-term commitment to change their day-to-day mobility habits.

Teamwork makes the commute work

For transport modes to integrate seamlessly together, relevant players must work together. That’s easier said than done, especially in large cities where often there can be several of public and private mobility operators. “From the outset,” Jens advised, “you have to map out all of the stakeholders and create a project that works across departments,” since cities don’t tend to have a dedicated department for mobility hubs.

Fortunately, city planners can build this kind of collaboration into the procedure. “What we’re seeing more and more of,” Jens noted, “is that cities are actually requiring integration in all sorts of tenders, for instance, for car sharing operators, shared e-scooters and bikes, as well as public transport, to receive public funding or special use permits.” As part of that process, cities can define specific requirements. For example, Jens and his team looked at how e-scooters and shared bikes benefit from parking rules and designated hubs over free-floating models so that they don’t clutter or block the pavement. This, in turn, can make mobility hubs more attractive since people know vehicles will be available there.

The pitfalls Jens identified largely stem from when coordination falls through. “By working in isolation, there’s a high risk that mobility hubs will fail because there won’t be enough interest in them. It’s like a self-fulfilling prophecy.” Examples include hubs that are constructed without an overarching plan in disjoint areas of the city or inaccessible areas or places where people don’t feel safe at night. The lack of synergy can also apply to timing, like why it’s crucial to get hubs up in running before new construction is completed so that new occupants are likely to move more sustainably from day one.

Only when all stakeholders are in sync can mobility hubs go beyond serving the “low-hanging fruit” and instead get a substantial share of the population out of their cars. “If done right,” Jens went on, “hubs can have a substantial impact on the number of cars and kilometres driven. When done at scale, as opposed to one or two hubs here and there, it can really change overall mobility habits, which we already see in the mobility data.”

Low pushback, low tech, and low cost

Jens stressed that mobility hubs need not tarnish public sentiment to make a dent in car dependency. “It’s a bit less challenging and controversial to build mobility hubs than to establish restrictions on car use because people don’t see hubs as a restriction; they see them as offerings.” Putting alternative transport options in place and promoting hubs can help overcome the inevitable initial resistance from neighbours who might be wary about going car-free. Jens argued that this gentler approach to hubs encourages “space to have a conversation later on about reducing car use.”

Hubs also don’t rely on shiny, futuristic technology. “Of course,” Jens explained, “you need excellent operators, be it for car sharing, bike sharing, charging infrastructure, or public transport. But that’s often something that those teams are taking care of because it’s in their own interest to make the platforms very seamless.” He insisted that apps can be low tech. “You don’t need any rocket science or cutting-edge technologies. Some cities originally thought, ‘Let’s put a screen somewhere where you can find all sorts of services.’ But we know that it’s common for screens to break after a short while. Sometimes printed information or QR code to a website at a bus stop is good enough.”

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, these initiatives won’t wreck city budgets either. “Hubs are not massive, million-euro investments,” Jens pointed out. “It’s about being more conscious about how to connect transport modes and filling in the gaps.” But what cities don’t invest in financially they must make up for in ambition and coordination. “Find somebody passionate to drive mobility hub projects. One fast way to get going is to launch tendering and special use permits for private operators so that cities don’t have to run the services directly.” In other words, if mobility hubs are the next big thing for cities, as Jens encouraged, they shouldn’t cost a big sum of money. “They’re relatively easy and fast to do because they make the most of what you already have.”

Adina Rose Levin

Adina Levin was born and raised in Chicago, and clocked in over 10 years in New York City before moving to Barcelona. As a freelance writer and creative strategist, she explores cities, culture, media and tech.

Jens Müller

Jens is a sustainable mobility expert with 15 years of experience. He holds a master’s degree in European economic studies and previously worked on transport policy in the European Parliament.