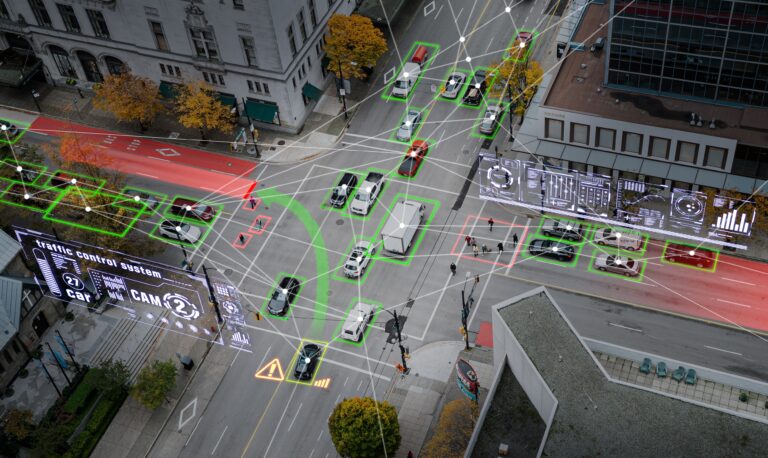

Admit it: Cars that drive without anyone in the driver’s seat often feel like something out of a sci-fi movie. Yet even as driverless cars become more common on the streets of cities like Phoenix and San Francisco, today’s vehicles still have a long way to go before they become fully autonomous. More importantly, autonomous vehicles (AVs) require changes in urban infrastructure that are already transforming our cities, beyond private transport.

To help us take a look under the hood on this topic, we chatted with Maria Kopp, a mobility consultant at Factual. She’s also the co-author of our free course on Autonomous Vehicles: An opportunity for Cities, where you can learn about AVs from A to Z!

The change you can see: safety, inclusion and the curb

As Maria said from the get-go, “One of the biggest topics people are concerned about is safety.” While crashes caused by driverless cars give us plenty of reason to be cautious, human error is responsible for 90% of car accidents. “People might be distracted while driving, make wrong decisions or not be in the best conditions for driving, and so on,” explained Maria. While it will take some time to get the technology completely up to speed, she said that “AVs can not only minimise but erase those human errors.”

AVs can also correct for shortcomings in inclusion and accessibility within our cities. As Maria pointed out, “There are people who cannot be as mobile as they wish to be or should be because current mobility systems are not capable of addressing their needs adequately.” When it comes to public transportation, for example, AVs can provide more flexible schedules and on-demand options because they don’t depend on driver availability. AVs can also be a source of additional routes to better connect rural areas.

Another key opportunity for driverless vehicles to improve cities’ infrastructure is parking. Unlike how typical cars remain parked 95% of the time, AVs don’t need to be parked unless they’re under repair, recharging or filling up with gas. “They could always be on the move,” Maria commented, “so we can liberate the parking space and make more efficient use of our vehicles,” with options such as car sharing. The downside? “That could also result in a lot of robotaxis constantly circulating and congesting the cities,” as Maria mentioned. “We need to make sure to have a broader vision of how we can use AVs sustainably.” All the more reason why integrating these points into policy is so important for AVs.

What’s in between the lines: policy and liability

While the aforementioned points are significant, they’re just “one piece of the puzzle,” said Maria. The way we currently plan urban infrastructure for the next 30 years will impact autonomous vehicles, and vice versa, as both planning techniques and technologies continue to develop. As the course covers in greater detail, most driving codes are based on two United Nations treaties — the 1949 Geneva Convention and the 1968 Vienna Convention — to address traffic rules, technical vehicle conditions and driving licences. Both are over 50 years old and have not been adapted to the nascent rise of autonomous vehicles, which are unlike the vehicles we’ve had on our streets up until now. In the meantime, individual countries have developed their own regulations and, naturally, they vary from region to region. That said, AVs themselves are sold worldwide, usually with the programming already built in, making it harder to determine who is responsible for following those local regulations.

“We no longer have just two stakeholders, the driver and the manufacturer,” Maria explained. “Now we also have people on the back-end who programmed and, in some cases, can take control of the vehicle if need be. The whole system is even more complex,” and the technology is still a work in progress. That makes it difficult to determine who will be accounted for in case of incidents because the vehicle’s decisions are prearranged to act and react in specific ways well before they hit the road. “So actually the liability for accidents and potential damages would already start there, with who, in the first place, decided when the vehicle is doing which movement and which principles we use actually to program automated vehicles.” However, we still don’t know what those principles look like in practice because the technology is still advancing and policy typically takes much longer to develop and implement. It’s a very complex issue and “there’s a big discussion on what needs to be regulated and decided on,” Maria added.

The bigger picture: getting everyone on board

To approach these challenges, it helps to, as Maria brought up earlier, broaden our perspective on AVs. “The fully autonomous vehicle, the Tesla, where you don’t even touch the steering wheel,” said Maria, “is what pops into most people’s minds.” (After all, historically, the car industry has a knack for storytelling.) Yet there are several different use cases beyond private vehicles where autonomous mobility technologies are incredibly important. “That’s maybe the most important message of the course,” Maria admitted. “We’re not just talking about a fully automated vehicle for private use because that doesn’t benefit the city, society or the environment as a whole.”

More specifically, we’re talking about public road transportation. Conventional buses that drive autonomously are being piloted in Madrid as part of the European project SHOW. Autonomous shuttles that feed into larger public transport networks or run on closed areas like airports, hospitals and campuses, along with smaller shuttles, on-demand robotaxis and other autonomous shared vehicles, are already being tested in different cities, said Maria.

If all that sounds expensive to you, you’re not alone. Maria asserted, “The investments needed for autonomous vehicles are very costly, which is a clear obstacle.” Then there are the time costs. “Regulation is a very slow process,” Maria added, “and as long as those regulations are not in place, it’s very difficult to get the permits to test autonomous buses in cities.” That’s why the infrastructure needs to be worth it for the public at large — and that’s where people like you and me come in.

Autonomous vehicles have generated a lot of scepticism, aside from safety concerns. Maria explained that it’s understandable that people would want to know “how AVs are going to be deployed and what that means for people who are currently working in driving positions like taxi drivers and bus drivers.” Automation and job replacement tend to go hand in hand, which is why AVs are a controversial topic. So as planners and other decision-makers attempt to close the gap in this sector, they also need to engage with everyday people and have them engaged in these discussions too.

“We need to make sure to have people on board and understand the technology,” Maria concluded. (You can start by taking our free course Autonomous Vehicles: An opportunity for Cities!) “Only then can we actually make AVs a beneficial mobility means of transport” as opposed to a sci-fi movie or commercial for Tesla.

Adina Rose Levin

Adina Levin was born and raised in Chicago, and clocked in over 10 years in New York City before moving to Barcelona. As a freelance writer and creative strategist, she explores cities, culture, media and tech.

Maria Kopp

Maria is a mobility consultant at FACTUAL with a background in urban and rural planning and is particularly interested in understanding commuting on a larger scale.